CANSFORD LABS

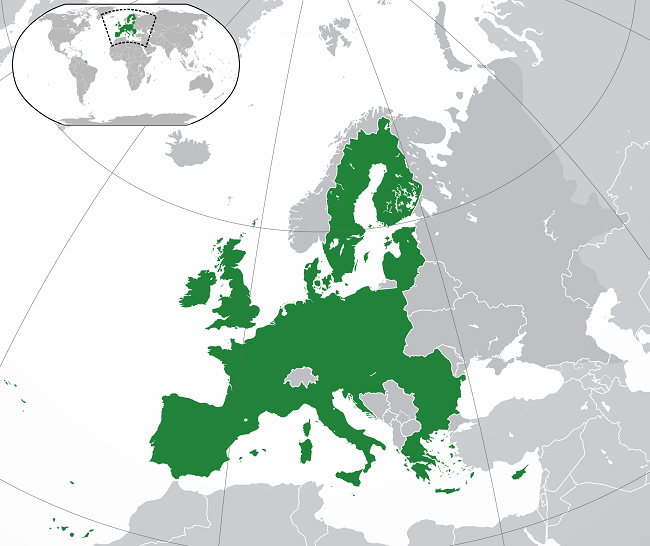

Understanding the workplace drug testing rules around Europe

on Jan 9, 2019

Workplace drug testing in Europe is a tricky business. The European Convention on Human Rights guarantees the right to personal privacy, but waives it for cases involving public safety, the prevention of disorder and crime, or the protection of health and morals - among others.

Further directives state that employers have a duty to ensure the health and safety of workers (at the employer’s cost), and they must consult workers on questions related to health and safety at work. Employees, meanwhile, are obliged to inform their employers of any serious and immediate danger to safety and health in the workplace - including their own.

However, putting these policy guidelines into practice is still a matter for member states and their national law. The specific interpretations of EU policy differ significantly from state to state, and a testing lab or legal practitioner working at international level must be aware of the nuances.

The UK

Workplace drug testing is legal here, but only under specific circumstances. Employers need employee consent to test for drugs either before or during employment, and usually secure this within contractual health and safety policies.

As a general principle, testing should be limited to those employees who need testing and random in nature, only singling out particular employees if their job role justifies it, or if there's reasonable suspicion that they've been using. Employers must also comply with data protection practices, as the results of drug tests constitute sensitive personal data.

Over the last decade, workplace drug testing has gone from a resisted “shabby trick by bosses” to a legally defensible option, becoming more widespread during 2014 and now an acceptable part of the working landscape within safety-critical industries. 17% of personnel directors - a significant minority - believe that alcohol consumption is a major problem for their businesses, and a massive 90% recognise it as an issue. Will testing become more widespread in less critical industries if more directors decide the issue warrants serious attention?

Ireland

In general, Irish companies only carry out workplace drug tests if stated in the contract. Section 13 of the Safety and Health at Work Act 2005 provides for the testing of employees suspected to be under the influence of intoxicants.

However, owing to pushback from the Irish Council for Civil Liberties and other bodies (who believe the legislation is too broad and contravenes basic rights to privacy), the Act’s guidance has yet to be implemented outside of specific cases like the Railway Safety Act (2005), which sets blood alcohol limits for train drivers.

- You may like: Workplace drug testing: Interview with Frank Bellwood

In the meantime, Irish employers have been advised to establish their own policies which balance their obligation to ensure a safe and healthy workplace with the privacy of individuals. Disciplinary proceedings are usually instigated on a basis of workplace performance reviews or risk, rather than the results of a drug test.

Ireland’s drug policy is still coalescing around the national strategy “Reducing Harm, Supporting Recovery”, which takes a relatively broad focus. Ireland is less interested in policing illicit drugs than in minimising the harm they do to communities, families and individuals. Evidence-based policies and actions are an integral pillar of the strategy, suggesting a potential role for workplace drug testing.

However, attempts to introduce random drug testing by the Dublin Port Company were blocked by the Irish Labour Court, on the grounds that there was no legal requirement for workplace drug tests. The Court went on to say that attempts to justify it “relied on broad statements in relation to the operation of the port”, and that “the impact of random intoxicant testing may affect other rights of employees.”

France

Workplace drug testing is legal in France, but only during employment: tests cannot be carried out before a contract is signed. Once in post, employees can be tested in accordance with the employer’s internal rules and regulations (so employers need to have a workplace drug policy in place), provided the influence of drugs is likely to cause a threat (e.g. if the employee drives a vehicle or handles hazardous products).

The test is performed by, and at the discretion of, an occupational doctor, who informs the employer of the employee’s ability to perform their duties - not the actual test result. Routine testing is prohibited and, crucially, employees are allowed to challenge the results of the test.

France has some of the strictest drug and addiction laws in Europe, directed by the Government Plan for Combating Drugs and Addictive Behaviours. The policy - which does not distinguish between hard and soft drugs, and treats all cases as a criminal matter - has been acknowledged as “inefficient” and “time-consuming” by a government report - and since the first laws criminalising drugs were passed, the number of drug users has steadily increased.

More cannabis is smoked in France than anywhere else in Europe, and just over half of the population would support government-regulated sale of the drug. The current government has introduced on the spot fines in an attempt to streamline the process, but has ruled out a softening of its baseline stance. On the whole, the workplace seems more liberal than the state.

Germany

Employers in Germany are entitled to request a drug test before a prospective employee signs a contract. The test requires the employee’s consent and, as in France, has to be carried out by an occupational physician, who informs the employer whether or not the employee is fit for work without disclosing the test result. Once employment has started, drug testing without the consent of the employee is generally not possible, although occupational and operating safety reasons can justify a one-off test.

Employers’ policies generally prohibit alcohol and drug use in the workplace, and many prohibit prescription drugs that are not required from a medical standpoint, if the drug use affects the employee’s work. Employees’ obligation to work (and thus contracts) are frequently terminated if these policies are obviously contravened.

These policies exist against a mostly liberal National Strategy on Drug and Addiction Policy, which helps individuals reduce or avoid consumption of licit and illicit substances. Germany reviews its drug situation through epidemiological studies, approaching addiction as a condition to be treated rather than a social problem to be policed. Drug use is generally on the rise, but only slightly - and the number of new treatment clients for high-risk drugs is also on the rise, suggesting that the focus on helping users govern their habits is paying off.

Sweden

The Swedish Labour Court (a body that exists to arbitrate disputes between employers and employees) accepts mandatory drug testing in workplaces where there is an objectively justified need (e.g. in the construction or security sectors), as long as employees are informed about the test well in advance.

Such tests can be carried out before or during employment. These tests should be systematic - i.e. not random or targeted, as this could constitute discrimination - and conducted in cooperation with the employee’s union. European lawyers recommend that employers establish their drug testing policies after consulting and agreeing with the unions involved.

Historically, Swedish employers have pushed for testing to be applied to all workers in all job types, to guarantee “business safety”. As long ago as 2005, 70% of the top Swedish companies had a policy of mandatory drug tests; 23% used unannounced drug tests. This mirrors an overarching concern in government policy - the Comprehensive Strategy for Alcohol, Narcotics, Doping and Tobacco aims to have a society free from narcotics and doping, and with reduced medical and social harm from even licit substances.

Italy

Since 2008, Italian law has prescribed mandatory drug tests for certain jobs which entail safety risks to others, setting out which drugs can be tested for and what procedures are to be followed. Employers have no discretionary power and cannot extend tests to other roles or drugs, although they can refuse to hire applicants who do not consent to an examination where one is mandated.

However, the number of true positives arising from these tests is low, while the frequency of false positives has been generally high: the researchers who identified this trend have advocated for a revision of Italian workplace drug testing law.

Drug use itself is not an offence under Italy’s Consolidated Law; possession for personal use is punishable by formal warnings, administrative sanctions (e.g. the loss of your driving licence), and potential rehabilitation and therapeutic programmes. The attention of criminal policy in Italy remains firmly on the supply of illicit drugs.

Slovenia

Slovenian law obliges employers to remove workers who are under the influence of drugs or alcohol in the workplace, in the interest of safety, but does not prescribe a specific test procedure. Therefore, it is the employer’s responsibility to establish a policy which determines how this legal obligation will be met - with workplace drug testing as an acceptable option, provided it is carried out by a professionally trained person.

Slovenia has been the site of long-term efforts by the UN and International Labour Organisation, along with other bodies, to prevent substance abuse and change the culture around drugs on a nationwide scale.

Early pilot schemes introduced a preventative approach, rather than the cover-up and dismissal if caught approach previously adopted. Testing has also been used by Slovenia’s Traffic Safety Agency to support campaigns against driving under the influence. More recent research has agitated for the extension of drug checks beyond Slovenia’s nightlife and roadsides, suggesting a potential growth in the use of workplace drug tests may be on the cards.

Portugal

In 2001, Portugal decriminalised consumption, acquisition and possession of drugs for personal use. When there is no suspicion of involvement in trafficking, drug use is the responsibility of local Commissions for Dissuasion of Drug Addiction, made up of legal experts, doctors, psychologists, sociologists and social workers. While sanctions can be applied at the Commission’s discretion, the main objective is to explore treatment needs and promote recovery.

In the workplace, drug screening of applicants and employees is generally prohibited. Examinations can only be carried out by a medical doctor, and only in order to establish fitness for work or the impact of work on physical health. The Portuguese Labour Code insists that employers and workers must respect each others’ right to privacy and confidentiality, including health matters.

Portuguese law on Personal Data Protection also has an impact here, stating that systematic registering of alcohol and drug control should not be a rule for all employees, but is justified for specific workers who put others’ health and safety at risk. Portuguese labour unions have developed interventions to combat the use of drugs in the workplace or working under the influence, building these preventions into their collective bargaining agreements.

Czech Republic

The Czech Republic fully decriminalised the possession of drugs following the collapse of its communist regime, but has since reintroduced penalties for “amounts larger than small”. Cannabis remains decriminalised for medical use, and has less strict penalties for possession, use and cultivation, reflecting an overall liberality regarding drug use in the country.

This said, intoxication at the workplace is strictly regulated. A 2006 amendment to the Czech Labour Code obliges employees not to abuse alcohol or other psychoactive substances at work or during working hours, and further prohibits arriving at work under the influence. Barring a handful of exceptions - where alcohol has to be consumed as a condition of work - this means Czech employers take a zero-tolerance approach.

Both legal professionals and the business community treat pre-employment drug tests as a must. Employers are permitted to conduct breath or saliva tests on their own premises, but only healthcare institutions have the right to take biological samples. From the employees’ point of view, refusing examination can be assessed as violation of working discipline - a firing offence. However, medical doctors are bound to secrecy, and can only give detailed information about test results with consent from the data subject.

General Data Protection Regulation

The General Data Protection Regulation is likely to have an impact on all workplace testing across the continent, redefining the rights of individual employees regarding sensitive personal data - such as anything related to possible drug use. Under the GDPR, data cannot be collected from an individual without consent or a permissible purpose. Crucially, employee consent for use of personal data by an employer is inappropriate, as the employer is in a position of power over the employee.

The permissible purpose for workplace drug testing under GDPR is more likely to be legitimate interest - i.e. when the interest of the employer in testing for drugs outweighs the fundamental privacy rights and freedoms of the employee. Workplace and public safety constitutes such an interest - broader policy and principle, however, do not. If there is a general rule that can be applied across the national jurisdictions making up the EU, that would be it.

Featured Image Credit: (CC) Wikimedia Commons

John Wicks

John Wicks is one of the UK's leading experts in drug testing and has been for over 25 years. He is CEO and co-founder of Cansford Laboratories, a drug and alcohol testing laboratory based in South Wales. John is one of the ‘original expert minds’ who alongside co-founder Dr Lolita Tsanaclis, is responsible for bringing hair testing to the UK.