CANSFORD LABS

5 ideas: the case for change to support UK children and families

on Oct 12, 2022

In his second exclusive 'long-read' blog for social workers, Richard Devine explores some lessons and ideas around how to help children and families. His ideas follow the Children’s Social Care Review, led by Josh MacAlister, who has published an interim report, titled ‘The Case for Change’.

Richard is a practising local authority Social Worker with children and families. He will be bringing his expertise, insight and experience to you on a monthly basis which we hope is informative, enlightening and interesting.

There are two common misconceptions when it comes to helping children and families in social work.

The first misconception is that social workers can make people change.

Unfortunately, though, we simply can’t. It might sound like an obvious point, but in my experience, we place inordinate expectations on ourselves to make parents change. Often this leads to us directly telling parents what the problem is and how they need to fix it.

However, telling parents what their problem is and how to resolve it is rarely successful. In fact, it can increase resistance and make change less likely to happen (Forrester, Wilkins, and Whittaker 2021). When these attempts fail, we can become frustrated, demoralized, and inclined to take the lack of progress personally.

The second misconception is that we can, through our relationship with parents, facilitate change.

Undoubtedly desirable, and perhaps a primary motivation for social workers entering the profession, yet, in my experience an unattainable ambition. We are a representative of a statutory organisation that is threatening to many parents. Anxiety, mistrust, and fear, whilst understandable responses to our involvement, causes tension, friction and breeds hostile ground for building relationships that make a difference.

In addition to the fear and anxiety generated by our involvement that persists even despite our best attempts to be compassionate and work in partnership with parents, we are considerably bound by time. This deprives the relationship of two key, evidential ingredients: psychological safety and time. Even if we have more time, and I certainly wish we did, I still don’t think our relationship can be meaningfully leveraged as a vehicle for change.

Our role is to engage in dialogue with parents that convey compassion for their situation, facilitate their willingness to change, and then provide the support services that maximise the probability of them being able to make the changes.

When change doesn’t occur, then we need to explain to them the possible responses that derive from our statutory duties clearly and calmly. Although I have only learned about Motivational Interviewing recently, I think it’s one of the most promising frameworks to support social workers develop the skills and tools to have these conversations.

In my opinion, the motivational interviewing approach needs to be aligned with the provision of support services such that the right support, relative to the intensity of the parent’s needs is available so that if, through dialogue, they persuade themselves into making change, the support that maximises the chance of them being successful is available.

%20no%20link.png?width=803&name=Family%20and%20child%20blog%20banners%20(2)%20no%20link.png)

An assessment is a co-constructed understanding of the family’s situation. The purpose of an assessment is twofold. Firstly, to clarify whether a child is at significant risk of harm and if so, provide an evidentially robust rationale that justifies statutory involvement. Secondly, it is an attempt to meaningfully understand the problem.

A good assessment provides a link between the problem and the solution

(Crittenden 2016).

Without it, we are unlikely to provide the type of support that will make a positive difference. Indeed, we may provide support that makes the matter worse. In terms of understanding the difficulties that parents we work face, the most useful framework I have encountered is the Dynamic Maturational Model developed by Patricia Crittenden.

It has revolutionized the way I understand and respond to the problems children and families experience. The DMM is a comprehensive model for understanding human behaviour and development across the lifespan.

It is a bio-psycho-social model that integrates many different theories and disciplines.

The DMM reflects over 3 decades of research on child protection populations and provides an understanding of how dangerous experiences, especially in childhood, profoundly shape and influence how to deal with thoughts, feelings, and relationships. Important ideas from the DMM model include:

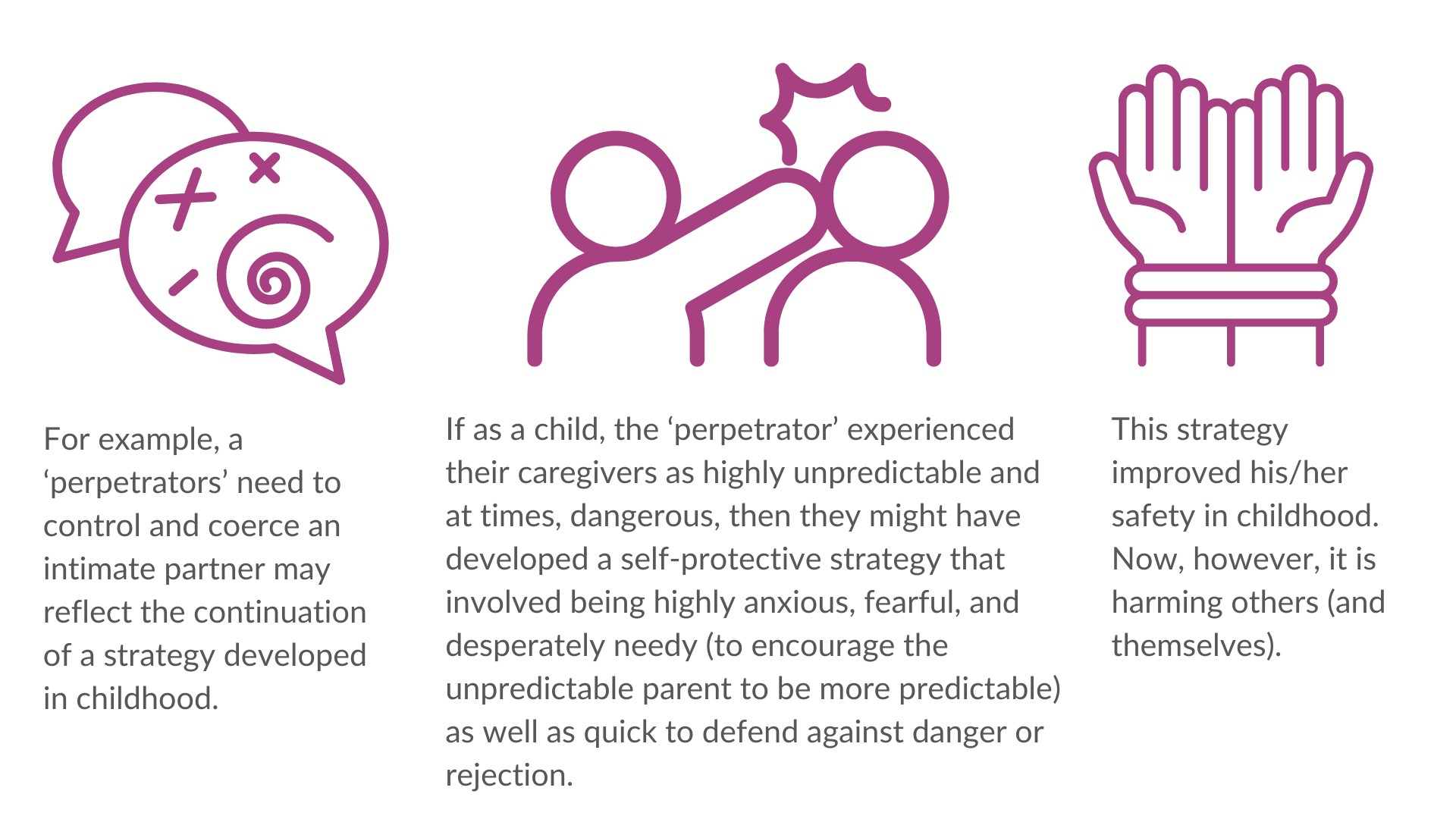

Attachment is a lifelong inter-personal strategy to deal with experiences, especially difficult ones. It influences perception as well as thoughts and feelings (intra-personal). Nearly all the parents I have worked with have been required to develop highly sophisticated self-protective strategies in childhood.

These strategies (ways of coping) are then carried forward into adulthood, albeit without awareness (usually because they operate unconsciously) and even though the childhood conditions that elicited them are no longer present.

From this perspective, dangerous parental behaviour is considered as misguided protective coping mechanisms that helped in childhood but when applied in adulthood cause harm to themselves and others. I think this helps provide an account for a large proportion of parents experiencing domestic abuse and parental mental health.

Understanding parents’ problems in this way could help us acknowledge the strength, courage, and ingenuity of a person’s survival strategy (Crittenden and Baim, 2017). Of course, we cannot condone the behaviour and we need to encourage adaptation. That is, helping them develop healthier ways of coping. However, this is more likely to be achieved when we begin by acknowledging their survival skills.

Children can tolerate and adapt to insensitive, inconsistent and/or mildly neglecting, rejecting caregiving without high risk of developing problems in childhood and/or adulthood. It is only when danger is introduced into the life of a child, particularly in the context of insensitive parenting, that the development of coping strategies that increase the risk of emotional, behavioural, and relational problems are needed.

What is danger? Domestic abuse, severe and poor mental health, chronic and/or heavy substance misuse, and trauma. This has, at least, two important implications. When working with children, ‘anxious attachment isn’t the problem, danger is the problem…change the danger, not the child’ (Crittenden, 2008: 21). Any intervention therefore that involves improving the developmental outcomes in a child’s life, should therefore prioritize minimizing the danger within in the child’s life. How do we do this? We help parents.

Asking parents to engage in a parenting programme (or family support intervention with similar aims) won’t address the issues for statutory involvement. Partly, because improving parental knowledge has ‘no effect … on the likelihood of abusing and neglecting behaviours’ (Landa & Duschinsky, 2013: 333), but also because ‘parenting issues’ aren’t ever the reason we are involved – not least because they don’t cause undue harm to children.

From an intervention point of view, we should therefore be endeavouring to minimize the danger within the family’s lives. We often tangle ourselves up with multiple difficulties experienced by a family and expect them to change too many issues at once.

For example, the use of drugs and/or alcohol by parents can often lead to chaotic home routines, inconsistent parenting, financial problems, including debt, poor mental health, and parental conflict. If we ask a parent to address their drug and alcohol use, there are few avenues in which to do this; 1:1 and group work through community drug and alcohol services, Alcoholics Anonymous or Rehabilitation Centres. This should be our primary focus.

Yet, often, we ask parents to engage in support to address their drug and/or alcohol use AND attend a parenting course for inconsistent parenting, engage in 1:1 family support to improve routines, attend the GP and access mental health support and engage in domestic abuse services.

As pointed out by Crittenden (2016: 285), ‘too many goals and too many professionals working toward the goals are likely to distract attention, generate anxiety about performance and change and obscure the critical aspects of the treatment’.

I have found it useful to conceptualise support as being divided into psychological (or individual) and sociological (family, community, professional). For example, if a parent is misusing drugs and/or alcohol, we encourage the parent to access treatment for their addiction (individual). This is where our relationship as social workers can be vitally important.

Our job is to engage in conversations that maximize the chance that parents will want to change, then function as a bridge between the parent and the services that will facilitate their endeavour in making those changes.

However, in addition, we should also support the family and their social network to mitigate the risk that stems from the parent’s issues, especially if the parents are unwilling to change.

This might include, for example, convening an FGC to look at the support the wider family could provide, or arranging for the child to access after-school-clubs or extra-curricular activities. This idea is beautifully illustrated in Working with Denied Child Abuse by Turnell and Essex (2006):

.png?width=924&name=Working%20with%20Denied%20Child%20Abuse%20by%20Turnell%20and%20Essex%20(2006).png)

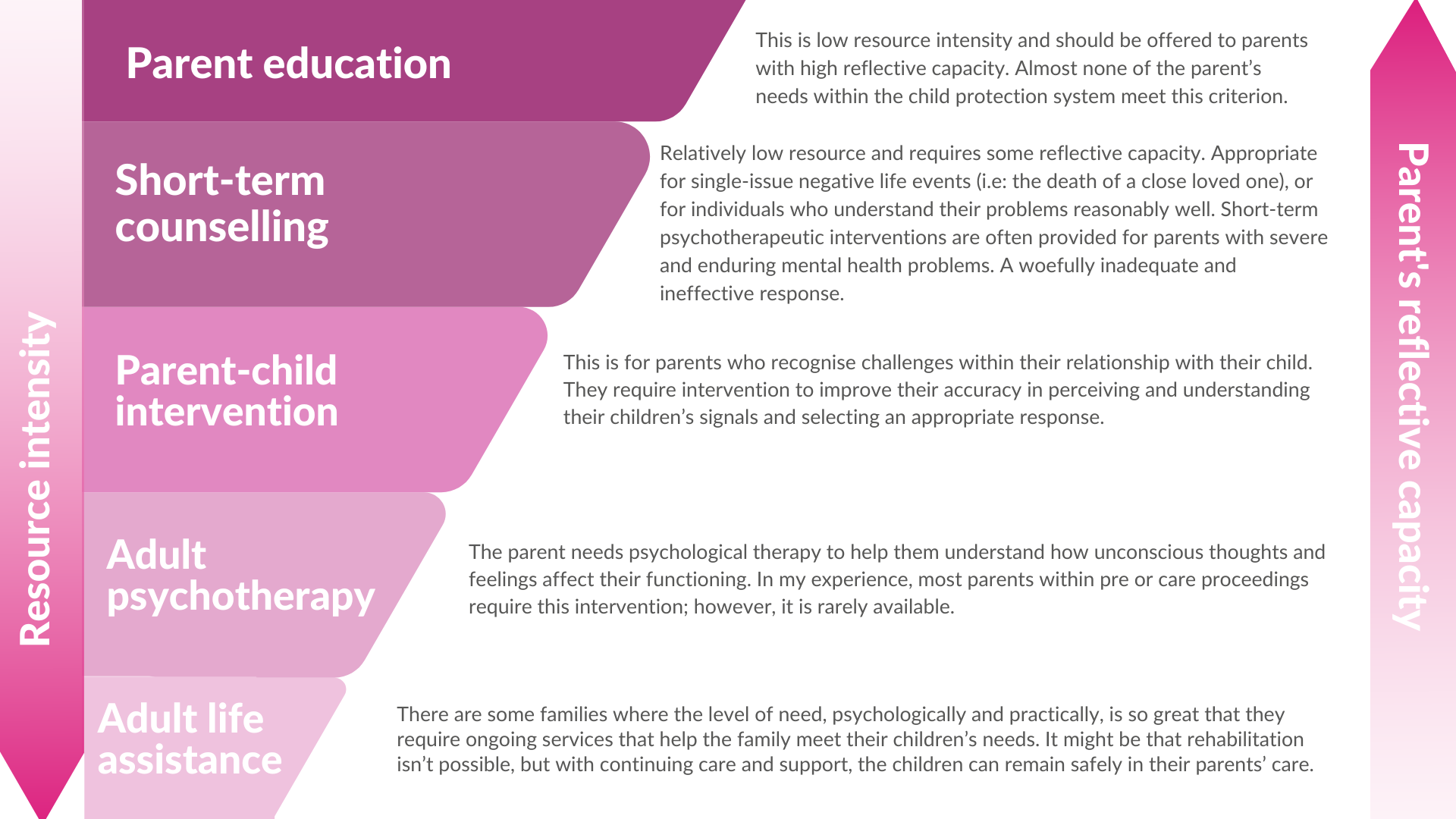

Another idea, derived from the DMM, is the gradient of interventions. A central idea from this model is that the intensity of the problem needs to be matched with the intensity of support provision.

.png?width=1024&name=Family%20and%20child%20blog%20banners%20(1).png)

Within my local authority, we recognize that many parents require psychotherapy, so we have begun funding parents to access treatment.

To increase the parent’s sense of control (and improve the first variable, willingness to access treatment) we provide an overview of the different modalities and invite them to select one. Then, we work together to identify a therapist, with care taken to ensure that relationally it’s a good match (thus accounting for the second variable, the quality of the relationship between the patient and therapist).

Of course, we recognize that a significant proportion of treatment success is dependent on extra-therapeutic factors, therefore any individual work needs to be situated within a broader framework of support.

Domestic abuse assessment and support

Our current conceptual understanding of domestic abuse is inadequate, outdated and leaves us bereft of meaningful solutions and support provision to help families experiencing this issue. I have found Johnson’s (2008) typology of domestic abuse especially instructive.

He proposed four types of domestic abuse, intimate partner terrorism, violent resistance, situational couple violence, and mutual violent control. The type of domestic abuse dramatically alters the type of response that should be provided. In practice, however, I have observed the typologies being unacknowledged. As a result, all domestic abuse cases, irrespective of the circumstances, are conceptualized as male-perpetrator, female-victim (or in Johnson’s terms, ‘intimate partner terrorism’).

Many cases would be more appropriately conceptualized as ‘Situational Couple Violence’, which isn’t characterized by coercion and control. Johnson identified several reasons for situation couple violence, including deprivation/poverty, disagreements on how to manage the children, alcohol and drug use, and verbal skills deficits. When we recognize that domestic abuse is caused by some of these factors, the potential for meaningful solutions becomes self-evident.

Even in cases where there is a clear perpetrator exercising coercion, control, and occasional violence, there is an absence of support, especially for women. In my opinion, men and women who engage in such interpersonal behaviour require long-term, intensive psychotherapy.

Psychological therapy

For the past few years, I have been using DMM-Adult Attachment Interviews as part of parenting assessments I complete. It has become apparent that many of the difficulties that parents experience stem from coping strategies developed in childhood and/or unresolved trauma.

For this reason, many parents would benefit from psychotherapeutic input to help them understand their experiences and develop healthier ways of coping (See Crittenden’s Gradient of Interventions). In these cases, parents’ problems would not be resolved by a 10-week parenting course or 6 weeks of talking therapy – although that is often what is provided. At the same time, I noticed a theme in the psychological assessments I read.

All of them recommended psychological treatment and nearly all of them said such treatment would take too long, and thus fall outside of ‘the child’s timescale’ - this is mentioned in my previous blog here.

Even if it didn’t fall outside of the child’s timescales, funding would be raised as an issue with children’s social care arguing that adult social care should pay for this and adult social care refusing.

Given that every psychological assessment recommends therapy, then, arguably, instead of commissioning a psychological assessment, we could bypass that process and simply use the same money (avoiding delay) and provide therapy.

An argument against this proposal might be that the psychologist identifies a particular therapy for the parent based on their assessment, therefore in the absence of an assessment, the wrong therapy could be offered. However, research into psychological therapy indicates that the main therapeutic modalities (MBT, Trauma-Informed CBT, DBT, etc) have undifferentiated efficacy rates (Johnson and Boyle, 2018a). It has also been argued by Professor Sami Timimi (cited in Johnson and Boyle, 2018b: 104), that ‘matching the model of treatment to a psychiatric diagnosis has an insignificant impact’.

Two important factors were relevant in the success of treatment. Firstly, the willingness of the individual to engage with the therapy, and secondly, the relationship between the individual and the therapist

(Johnson and Boyle 2018a, Sparks et al 2008, Wampold 2001).

Long term support and/or intensive support

Some family’s needs are so great that they require long-term support. I have written about this in detail elsewhere. As a result of the success of this approach, BANES are currently setting up a project, called Fostering Families (Crittenden and Farnfield 2007).

The principal idea is that for parents who are at risk of their children being accommodated, the foster family supports the whole family instead of just the children. Therefore, we avert the agonising and often irresolvable psychological distress derived from the parent and child separating.

Parental Advocacy

In my opinion, parental advocacy has the potential to contribute to the resolution of a long-standing problem. I will briefly detail the problem, then summarise how parental peer advocacy could assist.

Bekaert et al (2021) carried out a meta-synthesis examining 35 studies of family members perspectives of the child protection system. They found that many parents feel unduly pre-judged, disempowered, and confused by the worker and the child protection system. In turn, many parents responded with anger, upset, and confusion.

This could lead to despondency or resistance. When confronted with concerns about their child, some parents would feel attacked and react defensively. Other parents understood that compliance was rewarded, and therefore they would engage even if they didn’t think the plan would help their family to avoid negative consequences from children’s social care. Overall, family members felt the child protection system to be paternalistic rather than collaborative.

This complex interplay of factors renders parental engagement and participation a stubborn and difficult issue to resolve. The ongoing and seemingly insurmountable obstacles to effective participation manifest, despite the UK substantially increasing the implementation of different frameworks for practice (e.g. signs of safety, systemic practice, restorative approaches, motivational interviewing) in the past 15 years intended to improve relations between social workers and families in the child protection arena.

It has been argued, however, that ‘without adequate support, reframing practice can only achieve a particular and limited set of outcomes’ (Laird 2017, p.50). Even if social workers were extremely skilled, highly compassionate, and deeply empathic practitioners, there will always be a limit on how this will be received. Such an interpersonal approach will be filtered through a lens that parents often have of social workers being able to suddenly, and at any point, remove their children.

Therefore, different strategies for improving participation are needed instead of simply relying on individual social workers to change their practice (Kemp et al 2009, Featherstone et al 2018). I think parental advocacy has strong potential to be an effective solution to this issue.

Research into Parental Peer Advocacy has identified it as a promising approach in addressing and improving partnership and collaboration between the child protection system and families (Rockhill et al 2015, Bohannan et al 2016, Trescher & Summers 2020, Berrick et al 2011, Lalayants, 2014, 2017) and there is also tentative evidence to suggest that it improves outcomes for children (Tobis, Bilson, and Katugampala 2021, p.20).

Substance misuse

Treatment for parents with substance misuse issues needs to take into consideration the severity of the addiction. There should be a menu of evidence-based options for helping parents with substance misuse issues, including outreach drug and alcohol services, Alcoholics or Cocaine Anonymous, and Residential Treatment.

Asking a parent with a severe heroin dependency to attend an outreach drug service involving 1:1 sessions once per week alongside some short-term courses is unlikely to yield successful changes. Yet, this is what we often do.

In my opinion, when we enter pre-proceedings or care proceedings, Residential Treatment (or Treatment Centres, TC’s) should always be considered as a possibility. TC’s are highly structured residential programs that help individuals with drug and alcohol problems achieve abstinence. However, although abstinence is a key aim, it is focused on the whole person and to that effect, facilitates overall lifestyle changes. It provides one-to-one counselling, group work, psychoeducation, integration into a community where household tasks are shared and divided amongst them.

This supports psychological adjustment, socialization, and behaviour change. It usually lasts between 4 to 12 weeks, although the research is clear that the longer the treatment, the more effective it will be in achieving its desired outcomes (Gerstein 1990; Vanderplasschen et al 2014: De Leon 2010; National Institute for Drug Abuse 2015); in fact, time in treatment was the most significant predictor of success.

TC’s are more effective than other treatment modalities, especially for serious, chronic drug misuse problems (Gerstein 1990; De Leon 2010). Effective treatment can reduce drug misuse, criminal behaviour, and improve social functioning, such as wellbeing, employment, and psychological functioning.

For many parents we work with this would reduce the involvement of a range of services, including health, police, and social care. Dramatic improvements were made during treatment with some research stating that the reduction of crime and use of other services (health, social care) just while the person was in treatment meant that the TC ‘virtually pays for itself during the time it is delivered’ (Gerstein 1990, p.166).

The research highlighted that there can be some degree of deterioration upon discharge, however, over the years, this stabilizes. Even for those who failed to complete treatment, improvements (i.e. reduced drug use and criminal behaviour) were still noted.

According to a review by European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, five published economic evaluations found that whilst TC was expensive, this was compensated for by saving to society (Vanderplasschen et al 2014). De Leon, an internationally recognized expert on drug addiction and leading authority into research in therapeutic communities posits that ‘there is substantial evidence in support of TC treatment’ (De Leon 2010, p.42).

While Residential Treatment is expensive, any cost needs to be offset against the cost of children being removed from their parents’ care. Pause, an initiative to reduce rates of removal of children from mothers subject to recurrent proceedings, reviewed the costs of removal and care proceedings found the following: ‘The yearly cost savings attached to each child removal avoided are estimated at £57,102’. (Pause, 2017: 55). According to these figures, the cost for issuing care proceedings and removing a child costs £1,013 per child per week.

From the enquiries I have made, the estimated cost of 12 weeks at a TC is £10-12,000. That is the equivalent of the children being in care for 12 weeks, or if the parent has two children, 6 weeks. Furthermore, any cost incurred is proportionate to the likelihood of success. The research reveals that the dropout rate is high especially in the first few weeks, and within 12 weeks approximately half of those that attend, have dropped out.

However, those who remain in treatment and therefore cost the most, are those that are most likely to succeed in the longer term. For those that drop out within a few weeks, the cost will be considerably less. Cost aside, there is an important ethical case in being able to tell a child, if residential treatment is unsuccessful that we have done everything possible to support their mum or dad make the changes necessary to safely care for them.

Co-constructed Community Support

I have argued that parenting courses don’t improve outcomes for children subject to child protection plans or in the pre-proceedings process. With that said, they do have some value. When I have asked parents what they have found most useful about a parenting course, the response has been unanimous. They valued the social support and opportunity to share their struggle and difficulties with other parents on the course. Only occasionally has a parent talked about the content (i.e., techniques and ideas for parenting).

Therefore, I have wondered for some time how we can utilize the value of these courses with provision that is more sustainable and longer-term. Alcoholic Anonymous has been of interest, not least because it has helped family members overcome addiction, but more importantly because they have achieved a self-sufficient, leaderless, non-charitable, non-government funded, highly effective system of support

Perhaps we could co-opt the pre-existing infrastructure for delivering parenting courses into establishing these types of localized support groups. Initially, these will need to be organized by professional helpers alongside parents. The aim would be that parents who regularly attend, and as a result, overcome their difficulties, would be coached, and supported to run and co-ordinate these groups. There would be no waiting time and no need for a parent to exit the service.

Re-evaluate Family Support

In my opinion, we need a fundamental rethink and evaluation of family support in children’s social care. Family support workers come into the profession from a diverse range of backgrounds, experiences, and qualifications. A strength of this is that different experiences and skill sets mean that different workers can be matched to individual family needs. However, the vast majority of family support work in child protection tends to be limited to a few activities. These could be divided into four broad themes.

- Parent education.

- Relationship work between the parent and child.

- Practical Support (i.e., budgeting, charity applications).

- Emotional Support.

In discussions we’ve had with family support workers within my local authority, they’ve identified several challenges in their work. Firstly, the plan of work is given to them by the social worker, and not done in conjunction with the parents. Secondly, they are often asked to do work around routine and boundaries.

When they meet the family, however, it is soon evident that the parents have far greater and more urgent problems that they need help with (i.e., domestically abusive relationship, substance misuse issue, poor mental health, poor housing, etc.). Some of the more pressing and urgent problems, if resolved, would reduce the need for work around routine and boundaries.

Thirdly, while they recognise that parents would benefit from more intensive, longer-term emotional and practical support this is not encouraged or supported, nor do they have the time. Therefore, the work undertaken by family support workers tends to be heavily organized around parent education and improving the parent-child relationship.

Interestingly, when I have tried to find research and evidence on why we offer this type of support, I haven’t been able to find any (could someone help me?). I suspect that the type of family support we currently offer families has a limited impact, at least on the issues that warrant statutory involvement.

Despite the apparent lack of research in this area, the research undertaken in relation to recurrent care proceedings and the work undertaken by projects such as PAUSE reveals important insights and indicators into what might make a difference.

A key ingredient identified in the literature is having access to a long-term, reliable, highly supportive, emotionally attuned, and practically helpful relationship (Roberts et al, 2018: Barnard 2017: Broadhurst et al 2017: Cox et al, 2017). In other words, a ‘transitional attachment figure’ (Crittenden, 2016) that supports them address problems incrementally and at a tolerable pace for the parent. The transitional attachment figure can function as a bridge, being a link between the parent and the support services that can help.

For example, they build up a relationship with them over time and accompany them to their first AA meeting; help them understand and implement the advice of their mental health worker; support them access community resources and build up a social network. The work of Hilary Cottam detailed in Radical Help (2018) is relevant here.

To improve our understanding of what constitutes meaningful family support, at my local authority we have teamed up with Dr. Louise Brown from Bath University and are in the middle of a project. We are undertaking several fun (we hope!), creative, and engaging sessions with parents who previously had a child subject to child protection and had access to a family support worker.

The group will explore what was helpful, what wasn’t helpful and importantly, if they had an ideal family support worker what would they be doing. We hope this project will produce ideas and recommendations that will influence future practice.

In detailing these various forms of support, it is important to acknowledge the position that these ideas are being considered. I work with parents whose difficulties are such that there is a high risk of their children being removed unless significant change occurs. In other words, there is a high risk that without intervention, the Local Authority will issue care proceedings and the children might be placed in alternative care. As such, I am adopting an individualistic and interventionist approach.

The reason to make this explicit is because we should intervene in the lives of people with great caution. As pointed out by Crittenden (2016) outcomes in treatment are complex; sometimes they work, sometimes they work partially, sometimes they don’t work, and sometimes they make things worse.

This latter point highlights the need for children’s social care to be reflective about our involvement and think about whether it is helping or making it worse. There are, for example, some families who receive extensive support over many years, yet seem impervious to change. Nevertheless, they never quite reach the threshold for the LA to issue care proceedings. In these instances, Forrester’s advocation of ‘radical non-intervention’ should be considered. That doesn’t necessarily mean that we don’t offer help, but we remove the statutory component and its attendant burdensome and expensive way of intervening.

Finally, any endeavour to help children and family’s needs to be situated in a broader perspective – either a public health approach advocated for by Forrester, or a social model approach advocated for by Featherstone and colleagues (see here for debate on different perspectives).

For example, I think domestic abuse would benefit from a public health approach, as outlined by Leigh Goodmark, in her book, Decriminalizing Domestic Violence (2018). In between these more interventionist approaches and broader social policy initiatives, there are other ideas that I have not considered, such as FDAC and Family Safeguarding Model which are showing great promise.

Richard Devine

Richard Devine is a Local Authority Social Worker with over a decade of experience working with children and families.