CANSFORD LABS

Mother requires psychological therapy: Insights from a practising UK Social Worker in child care cases

on Sep 23, 2022

If the title of our blog sounds familiar to you as a social worker, (and you've experienced similar situations yourself) then we're delighted to introduce you to our new blogger, Richard Devine, who is a practising local authority Social Worker with children and families.

Richard will be bringing his expertise, insight and experience on a monthly basis through a series of 'long read' blogs which we hope you will find informative, enlightening and interesting.

An exploration of psychological assessments and recommendations: A Local Authority’s perspective

Richard recently gave a presentation at a conference chaired by the designated Family Judge for the region, His Honour Judge Stephen Wildblood QC. One section of the conference, hosted by the Local Family Justice Board, Avon, North Somerset, and Gloucester, focused on the use of experts in proceedings. In this blog Richard discusses and reflects on these issues as a practitioner, and his views and thoughts are entirely his own.

Practice experience

When I began social work in 2010, I was curious about how individuals had come to develop the problems that had led to social care involvement. As a consequence of growing up with my dad, who misused drugs and alcohol, I never conflated an individual’s morality or intrinsic worth with their behaviour, even when that behaviour was objectively destructive for themselves and/or others.

Whether a parent was suffering from depression or severe anxiety, misused drugs, and/or was controlling and coercive with their partner, I was intrigued by what they considered the benefits of such behaviour, and significantly, when it first emerged. For the latter question, I was always directed back to their childhood.

Consequently, I began looking at research and different theoretical frameworks to help facilitate my understanding of how childhood experiences impacted upon development in a way that led to individuals developing coping mechanisms that appeared self-destructive. I eventually came across the Dynamic Maturational Model of Attachment and Adaptation by Dr. Patricia Crittenden in 2014.

A central claim of the DMM is that most difficulties parents experience that result in their children being harmed are often the result of parents developing ways to cope in childhood in the face of extreme adversity and then misapplying the same strategies that kept them safe in childhood, in adulthood.

To give a brief example, a ‘perpetrators’ need to control and coerce an intimate partner may reflect the continuation of a strategy developed in childhood. Suppose, as a child, a ‘perpetrator’ of domestic abuse experienced their caregivers as highly unpredictable and dangerous.

In that case, they might have developed a self-protective strategy that involved being highly anxious, fearful, and desperately needy (to encourage the unpredictable parent to be more predictable) as well as quick to defend against danger or rejection. This strategy improved their safety in childhood. Now, however, it is harming others (and themselves).

Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) with parents

I subsequently began using the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) with parents. I found this tool to be the most effective way to understand how adults must cope with childhood experiences. Once I had a better understanding of the developmental and social context, the behaviour emerged, then the behaviour that seemed irrational, destructive, and incomprehensible made sense and subsequently seemed rational, self-protective, and comprehensible.

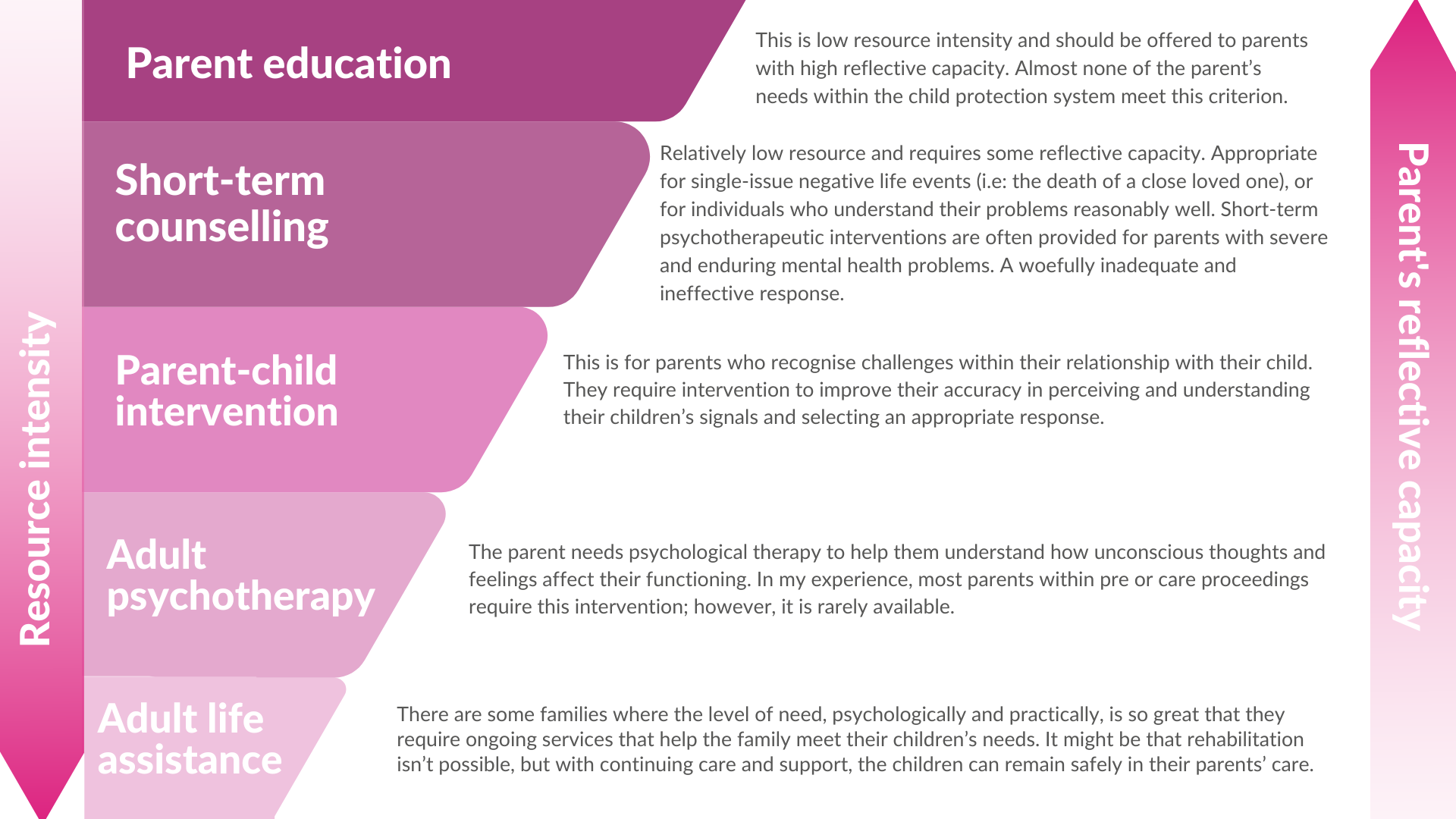

Drawing upon the findings from the AAI interview and another tool from the DMM, called the gradient of interventions, I realised that most, if not all, parents I was working with would benefit from psychotherapeutic input to help them understand their experiences and develop healthier ways of coping. A central premise of Gradient of Interventions is that the intensity of the problem needs to be matched with the intensity of support provision.

Psychological Assessments

At the same time, I was beginning to realise that most parents needed psychotherapy to overcome maladaptive self-protective strategies, I noticed a theme in the psychological assessments I read. They recommended psychological treatment, and nearly all said such treatment would take too long and thus fall outside of ‘the child’s timescale’.

Even if it didn’t fall outside the child’s timescales, funding would be raised as an issue with children’s social care arguing that adult social care should pay for this and adult social care refusing.

Given that every psychological assessment recommends therapy, then, arguably, instead of commissioning a psychological assessment, we could bypass that process and simply use the same money (avoiding delay) and provide therapy.

An argument against this proposal might be that the psychologist identifies a particular therapy for the parent based on their assessment; therefore, the wrong therapy could be offered in the absence of an assessment.

Psychological therapy

A colleague and barrister, David Barker (a very smart, wise, and kind friend who sadly died; he was a great inspiration for me and someone I looked up to) and I decided to investigate this further. We set out to undertake a literature review on the main psychological treatments, such as:

- Mentalization Based Therapy (MBT)

- Dialectal Behavioural Therapy (DBT)

- Trauma-Informed Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (TI-CBT)

- Cognitive Analytical Therapy (CAT), etc.

An unexpected surprise

We intended to find out rates of the efficacy of each treatment modality, draw up a table with the various types of therapy, and include a summary of the symptoms that each treatment purported to remedy. Our goal was to produce a summary table so that social workers could speak with parents about their symptoms and then match the symptoms with the appropriate therapy so that we could increase the chance of the appropriate therapy being offered.

However, to our great surprise, we learned that the research into psychological therapy demonstrates that the primary therapeutic modalities (MBT, DBT, TI-CBT, CAT, etc) have undifferentiated efficacy rates (Wampold and Imel 2015, Johnson and Boyle 2018a).

In other words, the different types of therapy produce similar outcomes. Even more surprising, ‘matching the model of treatment to a psychiatric diagnosis has an insignificant impact’ (Professor Sami Timimi cited in Johnson and Boyle, 2018b: 104).

Two critical factors were relevant in the success of treatment

Firstly, the individual’s willingness to engage with the therapy, and secondly, the relationship between the individual and the therapist (Johnson and Boyle 2018a, Sparks et al 2008, Wampold 2001).

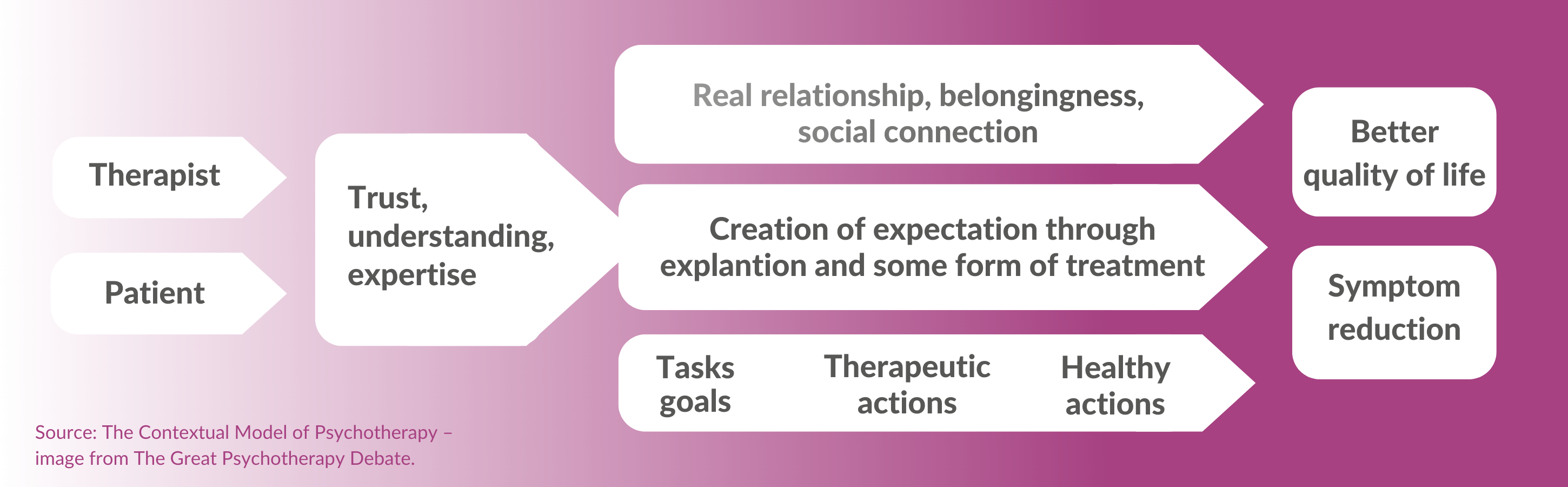

Regarding the latter point, the relationship with the therapist is a little more complicated in that there are three essential factors, but those three factors are consistently embedded in most organised, evidence-based therapies.

I will summarise the 3 factors identified as critical for psychotherapy success by Wampold and Imel (2015) in the Great Psychotherapy Debate.

Firstly, there must be some initial trust for the therapeutic relationship to be instigated. This is both instinctive and thought-out, or bottom-up and top-down. We make instinctive, rapid decisions about another person’s trustworthiness, which will influence the judgement a patient makes of a therapist (instinctive, bottom-up).

However, patients access a particular therapist based on other factors, such as a recommendation from a trusted friend, a review of the therapist’s credentials, cultural similarity, etc. These bottom-up and top-down processes contribute to the initial trust required for the therapy to begin.

Once the relationship has been established, there are:

What we have done at my local authority

Fortunately, I work in a local authority that has an innovative and, in my opinion, inspiring Assistant Director who has supported our attempts to understand these issues. They have also recognised the ethical and moral need to provide psychological treatment if that is suggested.

Funding parents to access treatment

So, we have begun funding parents to access treatment. To increase the parent’s sense of control (and improve the first variable, willingness to access treatment) we provide an overview of the different modalities and invite them to select one. Then, we work together to identify a therapist, with care taken to ensure that relationally it’s a good match (thus accounting for the second variable, the quality of the relationship between the patient and therapist).

Of course, we recognise that a significant proportion of treatment success is dependent on extra-therapeutic factors, therefore any individual work needs to be situated within a broader framework of support. In other words, psychological therapy should only be one piece of a puzzle of support.

BUT…What about the cost?

It is essential to point out that the cost is relative to the probability of success

Let’s say, hypothetically, as a Local Authority, and we decided to offer every parent who has a child subject to pre-proceeding psychological therapy.

A - most parents wouldn’t be ready to engage in the treatment; therefore, this would exclude a significant amount. And B - research illustrates a high dropout rate after the first session, and the second greatest chance of dropout is after the second session (Connell and Mullin 2006).

Therefore, only a few parents will want or be ready to access treatment, and even few will be able to attend consistently. Thus, those attending consistently will incur the highest costs, but they are also the ones where therapy is more likely to make a positive difference.

Humane and ethical cost

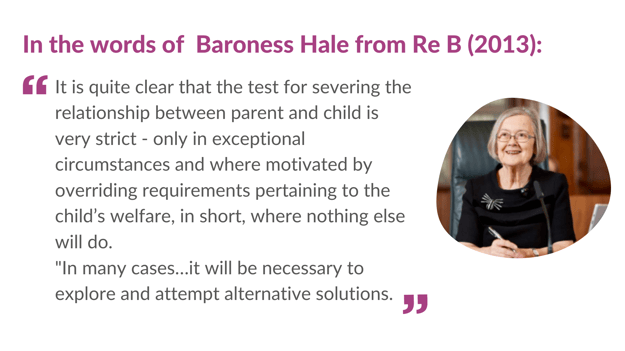

In addition to financial costs, we should also consider the humane and ethical implications of not providing treatment if required. I’ve been around long enough to experience the ripple effect that stemmed from Re B, which re-empathised the point that the court should only endorse a care plan when every other option has been tried and tested.

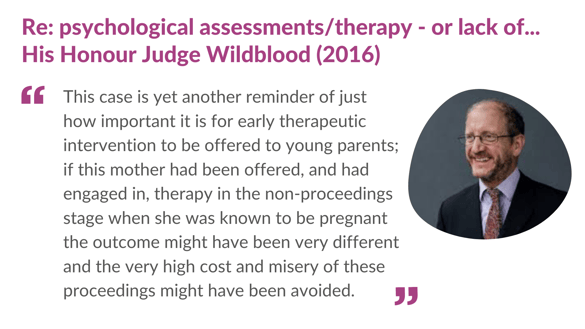

More specifically to psychological assessments, His Honour Judge Wildblood (2016) lamented several years ago his concern about not providing a parent with psychological therapy when, in all likelihood, it was self-evident that it would be required:

- The social worker’s role is critical in supporting the parent to understand the nature of their difficulties and helping them identify connections between past experiences and current functioning. The social worker essentially functions as a bridge between the parent and treatment and plays a vital role in supporting them to consider the need and value for psychotherapeutic input.

- Not all therapies are equal. We have found that parents who access counselling-type therapy tend to have less favourable outcomes. This is reflected in the research, which finds better outcomes for organised, structured therapy that involve the patient undertaking tasks rather than therapy that involves someone empathically listening, offering an unconditionally positive relationship (Wampold and Imec 2015). It is better than nothing but not as effective as other treatments.

- It doesn’t work for everyone. As pointed out by Crittenden (2016), outcomes in treatment are complex; sometimes they work, sometimes they don’t, and occasionally they make it worse. For example, parents with substance misuse issues are likely to benefit from a more specialist intervention, such as Alcoholics Anonymous, Cocaine Anonymous or a Residential Rehab.

- Therapy is not a panacea and must be offered alongside other support. Some parents need help addressing real-life concerns before they can consider therapy. One parent we worked with needed 20 hours of intensive family support for 18 months before she was ready to access psychological treatment.

..In conclusion..

Much research has been undertaken in what is now commonly referred to as ‘recurrent care proceedings’, particularly in the past decade. This has significantly improved our understanding and resulted in several specialist support services that have proved especially effective, most notably, Pause.

The research undertaken in this area, in my opinion, is particularly instructive in how we can help some parents. Broadhurst et al (2017: 15) state ‘our findings clearly confirm observations from a wealth of international that the following ingredients are critical in promoting change:

- Consistent relationship-based help

- Informal support

- And learning from experience

Therefore, applying this to mothers subject to recurrent care proceedings Broadhurst et al (2017) highlight that the three ingredients to effective help are:

- Women should be offered to specialist psychological intervention, especially if recommended in previous care proceedings

- A highly supportive and long-lasting relationship

- Support to improve the quality of their relationships with the children removed from their care, through direct or indirect contact.

These three ideas seem to be as relevant for many parents with children subject to pre-proceedings and care proceedings as they are for mothers subject to recurrent care proceedings.

To receive our newsletters and blogs please sign up and subscribe using our form at the top of this page. We promise we will not spam you or sell your information onward. Thank you.

Video by SHVETS production: https://www.pexels.com/video/woman-talking-to-a-therapist-7200767/

Richard Devine

Richard Devine is a Local Authority Social Worker with over a decade of experience working with children and families.